The Power of Questions (Core Post No 4)

How learning to ask good questions—and avoid bad ones—is the key to making smarter decisions.

We’ve covered Decisions (Core Post No 1) , Context (Core Post No 2), and Perspective (Core Post No 3) in our first three Core Posts. The final piece of our Financial Mastery Toolbox is Questions.

So, let’s get started with a question.

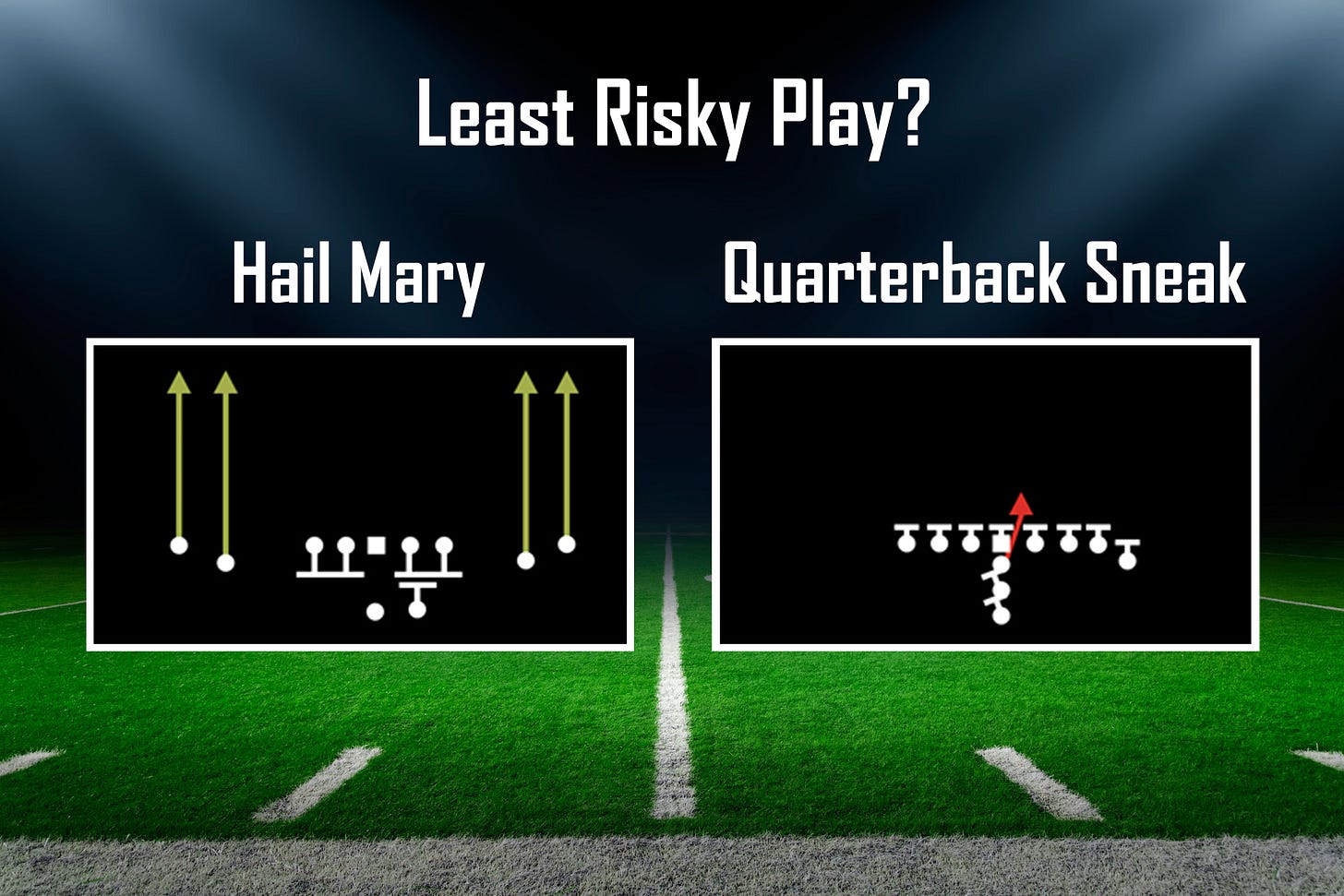

Which is the least risky play, a Hail Mary or a Quarterback Sneak?

Take a moment to think of your answer and then read on.

If you’ve read our previous posts, you probably realize this isn’t a straightforward question. In fact, it’s a bad question—and that’s the point.

So, did you answer one or the other? Or, did you recognize that you don’t have enough information?

We didn’t, for example, explain what we mean by risk. Our definition of risk throughout these post is:

The least risky strategy is the one that gives you the best chance of winning.

That’s a start, but it’s not enough. We also need a context. In this case, we need to know the score and the time remaining in the game.

Let’s try again.

Assume your team is on the 50 yard line, trailing by 5 points. There are 5 seconds left in the game. You have time for one final play and you need a touchdown to win.

Which play would you (and every coach in the history of football) call in this situation—which gives you the best chance of winning—a Hail Mary or a Quarterback Sneak?

Given this additional information, the answer is obvious: the Hail Mary.

An Investment Question

Let’s try another question:

Which is least risky, a Money Market Fund or a Stock Index Fund (say an S&P 500 Index Fund)?

Hopefully, you recognize that this is also a bad question.

We can use the same definition of risk: the least risky strategy is the one that gives you the best chance of winning (i.e., meeting your financial goals).

But what about the “game situation?”

We’ve touched on this before. If you need the money in 1 year, the Money Market Fund is least risky. Stocks lose money on a 1-year basis about 25% of the time.

But what if you’re investing for 15 years or more? In this case, Stocks are the least risky option—i.e., they give you the best chance of winning. Your chances of losing money (based on stock market history) are essentially zero. The market will go down during that period, but it will also recover.

And the chances of having a higher return on Stocks are very high. Stocks clearly put you in the best position to achiever your longer-term financial goals.

The “Loss” You Ignore (Because You Never See It)

In our simple example with only two investments, it’s obvious that being in stocks when the market goes down is not good. Most people view this as “losing money” (even if they don’t need the money anytime soon and, if they are patient, it will recover).

What’s less obvious is that being in a Money Market fund when stocks go up is equally damaging to your long-term financial well-being. It’s every bit as much of a “loss” as the first situation (except it’s a loss you won’t likely recover). The problem is that we don’t think of it this way (because we never see the numbers). Your 401(k) statement says nothing about how much more money you would have if you had made different, smarter, decisions.

We’ll go over this more later but, for now, just give this a little thought. As we’ll discover, being out of the market when stocks go up is a far greater risk that being in the market when the market goes down (for the simple reason that the market goes up far more often than it goes down).

The Moral of the Story

The moral of this simple exercise is to be careful when crafting your questions.

Albert Einstein once said (supposedly) that:

Questions are more important than answers.

What he meant was if you don’t get the question right, the answer won’t matter—and may even be harmful.

Unfortunately, like many things we’ll discuss, human nature gets in the way. When asked a question, we typically answer it (or try to answer it) without pausing to consider whether it’s a good question.

Once you have a good question, the next step is to make sure you have enough options. We tend to go with the first thing that comes to mind, but it’s often not the best option.

In our Core Post No 1 we noted that in a Choose Your Own Adventure book you are given at least two possible choices. This is a great help because it forces you to compare your options.

Your Homework Assignment

This obviously applies to more than investing. As homework, the next time you encounter a question, pause to evaluate whether it’s a good question. If not, refine the question until it is good—until it’s something that will help you make smarter decisions.

Then, give yourself at least two options.

This won’t guarantee you always make the best decision, but it greatly improves the odds.

What we’ve described isn’t difficult, it just takes awareness. Once this becomes a habit, you’ll be surprised how powerful getting the right question can be and how much it will help you with your financial well-being.

Stuart & Sharon

I really think is one of the best sections from you presentations!