The Three Muses

What I've learned from the three individuals who inspire me the most.

In Greek mythology, there were nine muses. Today we associate them with providing inspiration for music, poetry, and other forms of the arts.

In this post, I’m going to talk about my muses, my top three so to speak.

By the way, these posts are typically a collaboration between Sharon and me. Either one of us might come up with an idea or analogy. I generally research and write them and Sharon reads them to ensure they make sense and often offers suggestions regarding the graphics.

But not this time, because it just so happens she’s one of my three muses and doesn’t get a say in this one.

Richard Feynman

In no particular order, let’s start with Richard Feynman, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist and professor—who wasn’t much impressed with the award by the way. He said the pleasure of finding things out is the real prize.

One of my favorite Feynman stories is from when he was a boy and, on one occasion, other boys taunted him when he didn’t know the name of a particular bird.

Here’s the excerpt from his book, The Pleasure of Finding Things Out.

. . . one kid said to me, “See that bird, what kind of bird is that?” And I said, “I haven’t the slightest idea what kind of bird it is.” He says, “It’s a brown throated thrush,” or something, “Your father doesn’t teach you anything.” But it was the opposite: my father had taught me. Looking at the bird he says, “Do you know what that bird is? It’s a brown throated thrush; but in Portuguese it’s a . . . in Italian a . . .,” he says “in Chinese it’s a . . ., in Japanese a . . ., etcetera. “Now,” he says, you know in all the languages you want to know what the name of that bird is and when you’ve finished with all that,” he says, “you’ll know absolutely nothing whatever about the bird. You only know about humans in different places and what they call the bird. Now,” he says, “let’s look at the bird.”

From this story, I learned the value of noticing things and to explore them; not to merely name them. To that end, any conclusions we post are thoroughly tested.

You might think testing before publishing is the norm. It’s not. And I share Feynman’s disdain for what he called pseudo-experts.

We get experts on everything that sound like they're sort of scientific experts. They're not scientific, they sit at a typewriter and they make up something—may be true, may not be true, but it hasn't been demonstrated one way or the other. But they'll sit there on the typewriter and make up all this stuff as if it's science and then become experts on foods, organic foods and so on. There's all kinds of myths and pseudoscience all over the place.

I may be quite wrong, maybe they do know all these things, but I don't think I'm wrong. You see, I have the advantage of having found out how hard it is to get to really know something, how careful you have to be about checking the experiments, how easy it is to make mistakes and fool yourself. I know what it means to know something, and therefore I see how they get their information and I can't believe that they know it, they haven't done the work necessary, haven't done the checks necessary, haven't done the care necessary. I have a great suspicion that they don't know, that this stuff is wrong and they're intimidating people.

We see pseudo-experts in the financial world all the time, it’s pretty much the norm. Financial gurus need attention. They often don’t have the time to do the exhaustive work Feynman is talking about. It’s much easier to continue to repeat what others have said or to just publish provocative predictions.

I also admire Feynman’s ability to simplify complex concepts. He covered the basics of physics in his book Six Easy Pieces.

Later in life he was on a commission investigating the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. During his congressional testimony, he explained the problem with the O-rings, the cause of the explosion. He put a clamp on an O-ring and dropped it in a glass of ice water. After a few minutes, he retrieved it and removed the clamp. Because of the immersion in the ice water, the ring did not immediately revert to it’s normal shape. On the Challenger, it did not form a proper seal.

Prior to the launch, the coldest temperature at launch time had been 59 degrees Fahrenheit. On the day of the Challenger launch, it was 29 degrees.

The Morton Thiokol engineers attempted to share their temperature concerns to the decision-makers in charge of the go / no-go for the launch. Unfortunately, their report was rather dense and the conclusions less than obvious. That, and pressure to go ahead with the launch, contributed to the disaster.

From this, I learned to use analogies and other fun ways to get our points across.

Kate Bush

Kate is a British singer/songwriter, long held in the highest esteem by fellow musicians, but largely unfamiliar to an American audience until the song Running Up That Hill became a global phenomena after being featured in the Netflix sci-fi series Stranger Things.

Despite her brilliance Kate has generally avoided celebrity and is considered somewhat of a recluse.

Among the many things I admire about Kate is her work ethic and process. It would be fair to call her a perfectionist. She does things in her own way and in her own time.

She makes no attempt to follow the musical formula of the day—and it shows. Her music is eclectic and deep and, to be fair, a bit bizarre at times.

Not following the crowd is a trait we share with Kate. Much—probably most—of what you hear about investing is simply a rehash of what has been said before, much of which is wrong.

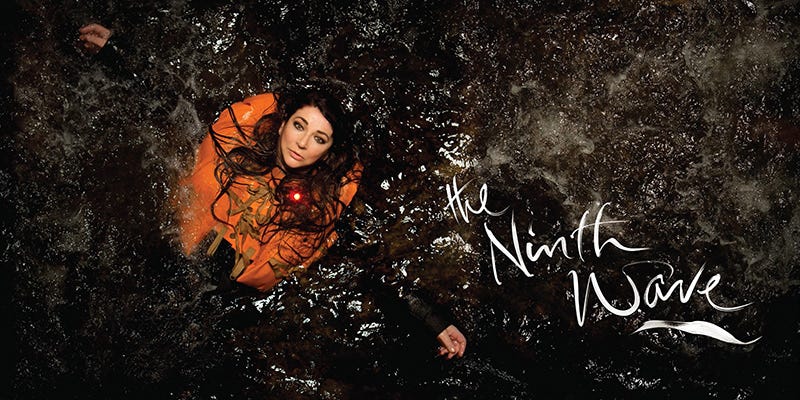

Her masterpiece (one of several) is the Ninth Wave suite which occupies the entire second side of her album Hounds of Love. The seven songs of the Ninth Wave tell the compelling story of someone lost at sea and their ultimate transformation upon being rescued. It is inspirational on multiple levels. Sharon and I named our company Ninthwave LLC, in honor of Kate and as a reminder that together we can face and overcome any challenges.

If you want another example, check this out.

The World Wide Web was invented by British scientist Tim Berners-Lee and the first web page was served on the open internet by the end of 1990.

We clearly weren’t all absorbed by our smart phones in 1989 and yet in that year Kate wrote Deeper Understanding with the opening line, “As the people here grow colder, I turn to my computer, And spend my evenings with it, Like a friend.”

Kate said she was inspired by a program she saw about Stephen Hawking (another of my heros) adding that she was “playing with the idea of how people get more and more isolated from humans and spend a lot more time with machines.”

This was decades before AI became mainstream. Just an incredible imagination.

Sharon Crickmer

Last, but not least, I have learned so much from Sharon since we started working together in 2001.

Sharon describes herself as a researcher. You can see this in her Instagram account An Adventure Shared.

When we travel, we both take photos of things that catch our attention. I rarely know the full story behind what we’ve discovered until I see Sharon’s Instagram post in which she summarizes what it is and why it caught our attention. She often follows this by sending links to her research and we discuss it in more detail. And—frequently—decide we need to go back for a closer look.

But she’s not just curious, she’s genuinely interested in other cultures and is an incredibly good listener. Yet she never imposes her views on others.

She is the best I’ve seen in front of a live audience. Before our live presentations, it’s not uncommon for her to have welcomed and talked with every participant in the room—and not about investments. She’s making connections that let people know she cares and continues this if she senses someone needs clarification during our sessions.

She’s somewhat of a rock star in India where she is routinely surrounded by participants who should be going on a break or leaving for another session but are curious to know more and seek her out for the opportunity.

While I’ve always been curious, I’ve learned from watching Sharon to—hopefully—be a better listener and to more actively observe what is around me.

Or, to borrow another line from Kate, to be, “Living in the gap between past and future.”

The Others

Of course, these are hardly my only sources of inspiration. I admire the works of Da Vinci (curiosity and perspective); of Einstein (imagination and child-like wonder); of Galileo (for having the audacity to claim the Earth revolves around the Sun and publishing his finding cleverly using the Socratic method); of Wisława Szymborska (check out her Nobel Prize acceptance speech or her poems, The Joy of Writing and Vietnam—what a staggering final line; of Betty Edwards (try her drawing upside-down exercise from Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain); of Amy E. Herman (check out her book Visual Intelligence then go to a museum and try out her exercises for improving your observation skills); of Stephen Fry (for his excellent and witty writing; I’m looking forward to his retelling of The Odyssey.)

And many, many more.

Stuart

(Don’t worry, Sharon will be back with the next post!)