What is a Bond? (Core Post No 9)

Yukon Cornelius and the basics about the world's most boring investment.

Bonds are boring.

If only we had a catchy song like Yukon Cornelius’s rendition of Silver and Gold in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

You know:

Silver and gold

Silver and gold

Everyone wishes

For silver and gold

How do you measure it's worth?

Let’s stop there. Silver and gold are commodities that can be used in an investment portfolio, and how you measure their worth is a topic for discussion, but not now.

When it comes to investing, there are three major asset classes that we need to explore before we look at alternative investments. They are: Stocks, Bonds, and Cash.

(And when we say Cash, we’re not talking about the paper money with pictures of presidents on them, but rather Short-term Investments. We’ll look at these in a future post.)

We’ve explored Stocks previously and we’ll get to Cash later, so let’s take a moment to look at Bonds.

Bonds are loans that can be bought and sold like stocks (which are shares representing ownership in a company).

Selling bonds became a way to finance various activities hundreds of years before stocks became a thing.

We can date the issuance of bonds at least back to the early 1100s when Venice issued the first recorded permanent bonds to fund a war against Constantinople.

Over time, bonds have financed the expansion of trade routes; wars; streets, water service, and sewage systems; railroads; industrial revolutions, and more.

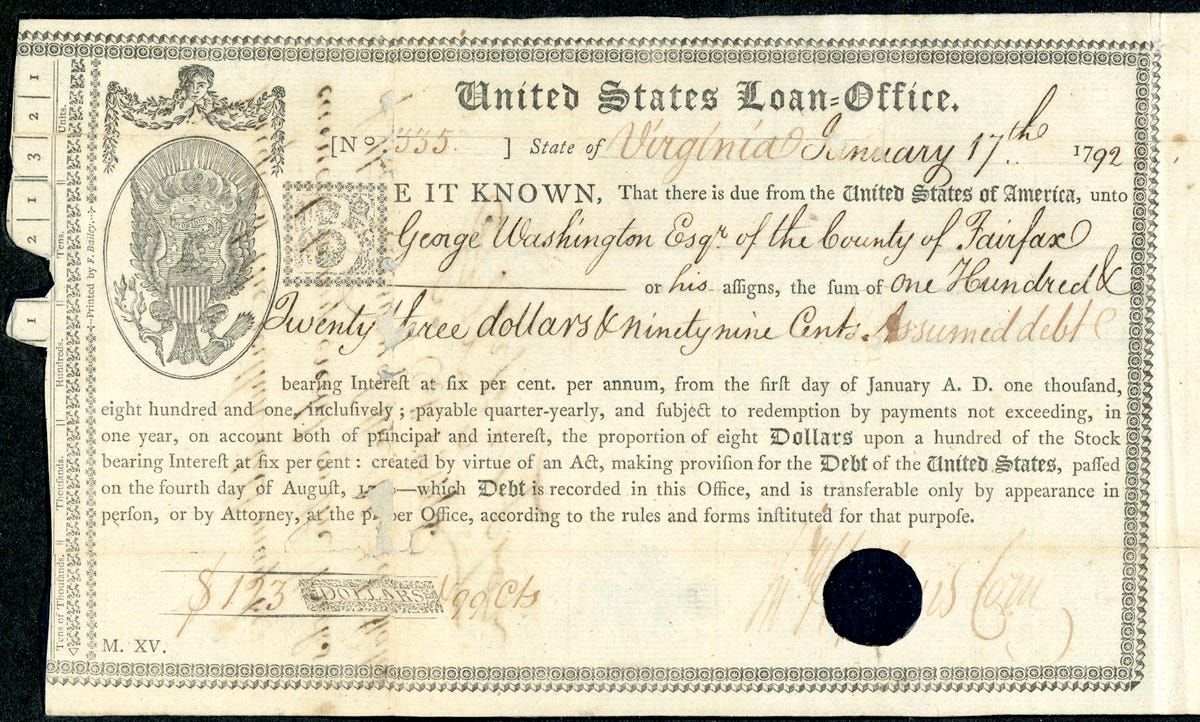

On January 17, 1792, President George Washington purchased the first US government bond (known as the Washington Bond) issued as part of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton's plan for liquidating the debt of the individual states and funding the national debt.

And while bonds become more interesting when we tie them to historical events, our only real goal of this post is to explain what a bond is.

Let’s stick with bonds issued by the US Government.

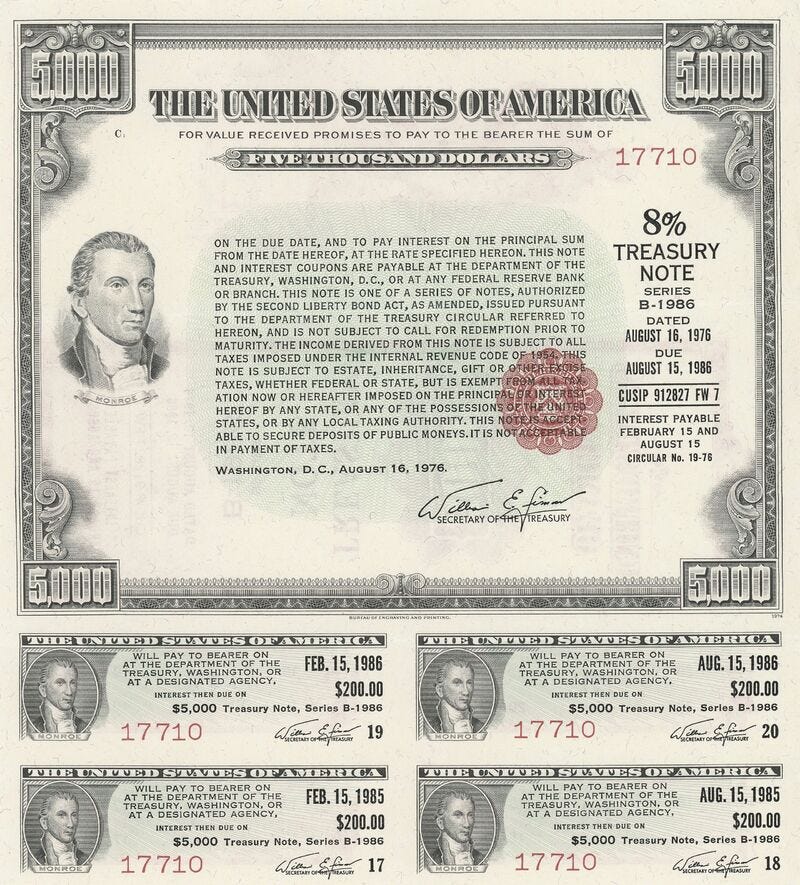

Below is an image of a 10-year US Treasury Note with a face amount of $5,000 that was issued via auction on August 16, 1976. (The US Government regularly issues bonds with maturities up to 30 years.)

Investors could have purchased this bond for its face amount of $5,000 (or possibly slightly more or less depending on the results of the auction) and redeemed it for $5,000 ten years later.

The bond pays a fixed interest rate of 8% per year, payable every six months.

Since 8% of $5,000 is $400, this means every semi-annual interest payment is worth $200 (which you can see printed on the coupons).

For years, investors would clip “coupons” attached to the bond certificate and redeem them for the amount of the interest payment.

Of course, there are no longer physical certificates and coupons these days—it’s all done electronically—but we still refer to the fixed interest rate that a bond pays as the “coupon rate.”

So, basically, we can describe a bond by noting it’s issuer (US Government, etc.), issue date, maturity date, and coupon rate.

Buying and Selling Bonds

Investors can buy individual bonds issued by governments or corporations, but the easiest way to invest in bonds is through mutual funds or exchange traded funds.

Bond funds are generally identified by the type of issuer and the average maturity of the bonds contained within the fund, e.g., short-term government bond fund, intermediate-term AAA corporate bond fund, or long-term aggregate bond fund (a mix of different issuers).

Bonds can be bought and sold like stocks from the time they are issued until the time they mature. Bond funds, of course, don’t mature and work pretty much like a stock fund.

Possibility of Default

If the issuer of a bond cannot afford to make the interest or principal payments, they may default on the bonds and investors could lose some or all of their money.

There is a wide range of creditworthiness with bonds, ranging from US Government bonds (considered the safest from a credit perspective) to high-yield bonds issued by governments or corporations whose creditworthiness is a bit dodgy.

Fixed Income Securities and Interest Rates

For most bonds, the annual interest rate is fixed when the bond is issued. That’s why bonds are often called “fixed-income securities.”

There are other, more complicated bonds where this isn’t the case. We’ll cover them in future posts.

When a bond is issued, the interest rate—i.e., the coupon rate—depends on where interest rates are in the world at that time.

Many factors go into this including how central banks, like the Federal Reserve, are dealing with balancing the challenges of inflation and recession (as we discussed in our post Between Inflation and Recession).

For now, just know that the interest rate the US Government pays is the lowest for any US entity issuing bonds for a given maturity. Corporations, for example, have to pay a higher level of interest to borrow money based on their creditworthiness.

Risk, Return, and How to Use Bonds in a Portfolio

There’s more to know about bonds, but we’re going to stop here for now.

If you grasp the concept of how a bond is structured: issuer, maturity, and interest rate, that’s a good start.

We’ll cover the risk and return of bonds and how to use them in a portfolio in a later post.

A New Jingle?

But before we go, let’s at least consider how Yukon Cornelius might have introduced a generation of children and adults to long-term investing.

Stocks, Bonds, and Cash

Stocks, Bonds, and Cash

Everyone wishes

For Stocks, Bonds, and Cash

These are the assets to take you

Down your retirement path

Stuart & Sharon